CHAPTER I

Legal issues connected with the Palestine problem

6. The problem of Palestine involves certain legal issues which it is essential to decide authoritatively before any solution consistent with international law and justice can be reached. The problem of Palestine necessitates a proper interpretation of the claims of Arabs and Jews to Palestine. The solution of the problem also raises various legal points as to the legality of any proposal for the future of Palestine, as well as the competence of the General Assembly to make and enforce recommendations in this regard.

Failure of the Special Committee to consider certain legal issues

7. The claims of Arabs and Jews to Palestine are examined in paragraphs 125 to 180 of chapter II of the report of the Special Committee.UN2 That Committee, however, failed to consider and determine some issues and juridical aspects of the Palestine question, and came to wrong and unjustified conclusions in relation to other matters which it did consider. The Special Committee did not consider the validity of the Balfour Declaration, nor the meaning of the term "Jewish National Home”, nor the validity and scope of the provisions of the Mandate for Palestine relating thereto. It also evaded the issue of the pledges made to the Arabs. It is apparent from the report of the Special Committee that the basic premise underlying the partition plan proposed by the majority of the Committee, and set forth in chapter VI of its report, is that the claims to Palestine of the Arabs and the Jews both possess validity. This pronouncement is not supported by any cogent reasons and is demonstrably against the weight of all available evidence. These facts take away a good deal from the reliability and authoritativeness of the Special Committee’s report, and vitiate some of its most important findings.

8. A number of speakers who took part in the general debate in the Ad Hoc Committee laid stress on the legal and constitutional issues connected with the problem of Palestine and on the powers and competence of the General Assembly to deal with the problem and to recommend and enforce any specific solution. Proposals were also submitted by three delegations suggesting that the advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice should be sought regarding some of the legal issues connected with the problem of Palestine. The Sub-Committee has therefore considered it necessary to review the main legal issues involved, and to state the points on which the opinion of the International Court of Justice should be obtained before a solution just to all parties can be evolved.

Back to topPledges made to the Arabs during the First World War

9. The claim of the Arabs to Palestine rests upon their centuries’ old possession and occupation of the country and their natural right to determine their own future. This claim is further supported by the pledges given to <273>the Arabs by the British Government during the First World War. These pledges were set out in the correspondence between Sir Henry McMahon and Sherif Hussein of Mecca, followed and explained by the Hogarth Message, the Bassett Letter, the Declaration to the Seven, General Allenby’s communication to Prince Feisal and the Anglo-French Declaration of 1918.

Palestine was included within the territories which Sherif Hussein claimed should become independent at the end of the war. It has subsequently been alleged, however, on behalf of the British Government, that the Government intended that Palestine should be excluded from those territories and that that intention was made known to Sherif Hussein. But that contention is negatived both by the wording of the McMahon-Hussein correspondence and by the subsequent communications and assurances communicated to Sherif Hussein on behalf of the British Government. There is a passing reference to this question in the report of the Special Committee, but the Committee failed to examine it in detail or to record its considered views on it. This Sub-Committee feels that the controversy regarding the interpretation of the McMahon-Hussein correspondence and the subsequent declarations can be satisfactorily settled only by obtaining the opinion of an authoritative and impartial judicial tribunal such as the International Court of Justice.

Validity and scope of the Balfour Declaration and the Mandate

10. The Jews, on the other hand, rest their claims regarding Palestine on the Balfour Declaration, which was subsequently embodied in the Mandate for Palestine. The Balfour Declaration has been attacked by the Arabs as being invalid on several grounds, inter alia, that it was made without their consent or knowledge, that it was contrary to the principles of national self-determination and democracy and that it was inconsistent with the pledges given to the Arabs before and after the date it was made. Although the question at issue regarding the legality, validity and ethics of the Balfour Declaration was specifically raised by the Arab Higher Committee at the special session of the General Assembly as the first issue to be inquired into, the Special Committee neither inquired into it nor expressed any opinion on it. It did not even mention it as being part of the Arab case. It is therefore essential that the question of the validity of the Balfour Declaration should be referred to the International Court of Justice for an opinion.

11. The next question that arises is the proper connotation of the term “Jewish National Home”, as used in the Balfour Declaration and subsequently in the Mandate. No definition of that term was contained in either of those documents. It is, however, clear that the Mandatory Power has never interpreted this expression as meaning the setting up of a Jewish State. If the term “Jewish National Home” means no more than a cultural centre which does not affect or diminish the rights and position of the indigenous population of Palestine, then no insurmountable difficulties arise regarding the interpretation of the Mandate. On the other hand, if the term “Jewish National Home" is to receive a retrospective interpretation which would derogate from the rights and position of the indigenous population, or result in the establishment of a Jewish State in Palestine, various question regarding the validity and legal interpretation of the Mandate would have to be resolved. These issues may be summarized as follows :

(a) The incompatibility of the two main objectives of the Mandate as expressed in article 2, as well as the inconsistency between the provisions of the Mandate regarding the establishment of a Jewish National Home in Palestine and those of the Covenant of the League of Nations regarding the preservation of the rights and the advancement of the indigenous population of the country;

<274>(b) The effect of the dissolution of the League of Nations on the Mandate;

(c) The extent to which the undertaking regarding the establishment of a Jewish National Home in Palestine may be said to have been carried out;

(d) The legal consequences arising from the declared intention of the Mandatory Power to withdraw from Palestine at an early date.

Views of the Sub-Committee on the legal issues

12. The Sub-Committee carefully considered the issues enumerated above and its conclusions are set out below.

(a) Article 2 of the Mandate required the Mandatory Power to ensure the establishment of a Jewish National Home in Palestine and at the same time to safeguard the civil and religious rights of all the inhabitants and to develop self-governing institutions in that country. Article 6 required the Mandatory to facilitate Jewish immigration under suitable conditions and to encourage Jewish settlement on the land while ensuring that the rights and position of the other sections of the population were not prejudiced. The experience of the working of the Mandate for twenty-five years has shown that these objectives are incompatible, and the Mandatory Power has reached the conclusion that it is not possible to give effect to the conflicting obligations imposed by the Mandate. That was made clear by the representative of the United Kingdom at the 15th meeting of the Ad Hoc Committee held on 16 October 1947.

Moreover, the Mandate must be considered in the light of and subject to the provisions of the Covenant of the League of Nations. According to Article 22 of the Covenant, the people of Palestine were one of the communities formerly belonging to the Turkish Empire whose existence as an independent nation was provisionally recognized by the League of Nations, subject only to the rendering of administrative advice and assistance by the Mandatory Power until such time as it was able to stand alone. The Covenant emphasized that the well-being and the development of the indigenous population of the country formed a sacred trust of civilization and the primary responsibility of the Mandatory Power. In other words, the only limitation upon the sovereignty of the people of Palestine was the imposition of a temporary tutelage under the Mandatory Power. It cannot be suggested that the entry of an unlimited number of Jewish immigrants into Palestine, or the creation of a Jewish State against the wishes of the majority of the people of that country, was in accordance with the aims and objectives of the Mandate and the principles embodied in Article 22 of the Covenant.

(b) In accordance with the preamble of the Mandate. Great Britain undertook "to exercise it on behalf of the League of Nations". That provision was also in accordance with the principles embodied in paragraph 2 of Article 22 of the Covenant. The operation of the Mandate was further made subject to a periodical review by the Permanent Mandates Commission. With the dissolution of the League, the principal party to the transaction has ceased to exist, and with it has disappeared the legal basis for the Mandate. The fate of Palestine must therefore be settled by the people of Palestine.

(c) The possible interpretations of the term "Jewish National Home" have already been mentioned in a preceding paragraph. In the view of this Sub-Committee, the only interpretation consistent with the objectives of the Mandate and the principles of the Covenant is that the Jewish National Home is a cultural home for a limited number of Jews and that it cannot imply any grant of sovereignty to them over any part of Palestine, or a derogation from the civil, economic, political and religious rights of the indigenous population of the country. This is borne out by several statements of the Mandatory Power, which itself issued the Balfour Declaration. In <275>this connexion, reference should be made to paragraph 15 of the statement of policy issued by the British Government in 1939, in which it declared:

“His Majesty’s Government are satisfied that, when the immigration over five years which is now contemplated has taken place, they will not be justified in facilitating, nor will they be under any obligation to facilitate, the further development of the Jewish National Home by immigration regardless of the wishes of the Arab population.”

The Ad Hoc Committee will also recall the statement made by Mr. Creech-Jones, the representative of the United Kingdom, at its 15th meeting on 16 October 1947, in which he declared that, in spite of various difficulties, a National Home for the Jews had been established in Palestine.

(d) It has already been pointed out above that, with the dissolution of the League of Nations, the legal basis for the Mandate has disappeared, and that the United Kingdom is exercising only a de facto authority in Palestine. With the recent declaration of the Mandatory Power, re-affirmed by its representative at the meetings of the Ad Hoc Committee, that it intends, in the very near future, to withdraw from Palestine and relinquish the Mandate, there is no further obstacle to the conversion of Palestine into an independent State. In effect, this would be the logical culmination of the objectives of the Mandate and the scheme for the development of nonself-governing territories embodied in Article 22 of the Covenant.

13. In the preceding paragraphs, an indication has been given of the views of the Sub-Committee on the principal legal issues connected with the interpretation of the Mandate and the Covenant of the League of Nations but, having regard to the fundamental importance of this question and to the fact that the Sub-Committee has already recommended that the advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice should be obtained regarding the pledges made to the Arabs during the First World War and the validity and scope of the Balfour Declaration, it is suggested that the International Court of Justice should also be requested to advise on the interpretation, the scope and the validity of the Mandate.

Mode of termination of the Mandate

14. The next question which arises is the constitutional method for the termination of the Mandate. This might be viewed from three angles:

(a) The termination of the Mandate in accordance with its own provision as read with the principles of the Covenant, assuming that the League of Nations had continued to exist;

(b) The termination of the Mandate having regard to the dissolution of the League of Nations; and

(c) The termination of the Mandate in the light of the provisions of the Charter of the United Nations.

15. The Sub-Committee considered all three aspects of this important question and its views are given below.

(a) It will be recalled that the object of the establishment of Class A Mandates, such as that for Palestine, under Article 22 of the Covenant, was to provide for a temporary tutelage under the Mandatory Power, and one of the primary responsibilities of the Mandatory was to assist the peoples of the mandated territories to achieve full self-government and independence at the earliest opportunity. It is generally agreed that that stage has now been reached in Palestine, and not only the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine but the Mandatory Power itself agree that the Mandate should be terminated and the independence of Palestine recognized. The only proviso deserving mention is that, under article 28 of the Mandate, the League of Nations was empowered to make such arrangements as might be deemed ne-<276>cessary for safeguarding the rights secured by articles 13 and 14 regarding the Holy Places in Palestine, and for using its influence to ensure that the government of Palestine would fully honour the financial obligations legitimately incurred by the administration of Palestine during the period of the Mandate.

The Mandate for Iraq was terminated in 1932 when the League of Nations was still in existence. The procedure followed was for the Mandatory Power to negotiate a treaty with a government representing the people of Iraq, and to Sucre the formal confirmation of the Council of the League of Nations, and the subsequent admission of Iraq as a Member of the League. This precedent, however, is not applicable to the case of Palestine, as the League of Nations and its Council are no longer in existence, and there is no international body which has inherited its powers and functions.

(b) It has been explained that, with the dissolution of the League of Nations, the legal basis for the Palestine Mandate has also disappeared, and that the Mandate must be considered to have come ipso facto to an end. But even if it is assumed that the Mandate is still technically in force, the appropriate manner of its formal termination would be by way of transfer of power from the Mandatory Power to a government representing the people of Palestine. The Mandatory Power would thus be following the recent precedents of Syria, Lebanon and Transjordan.

(c) Before considering the effect of the provisions of the United Nations Charter on the Mandate, it should be pointed out that the United Nations Organization has not inherited the constitutional and political powers and functions of the League of Nations, that it cannot be treated in any way as the successor of the League of Nations in so far the administration of mandates is concerned, and that such powers as the United Nations may exercise with respect to mandated territories are strictly limited and defined by the specific provisions of the Charter in this regard.

Competence of the United Nations

16. A study of Chapter XII of the United Nations Charter leaves no room for doubt that unless and until the Mandatory Power negotiates a trusteeship agreement in accordance with Article 79 and presents it to the General Assembly for approval, neither the General Assembly nor any other organ of the United Nations is competent to entertain, still less to recommend or enforce, any solution with regard to a mandated territory. Paragraph 1 of Article 80 is quite clear on this point, and runs as follows:

“Except as may be agreed upon in individual trusteeship agreements, made under Articles 77, 79, and 81, placing each territory under the trusteeship system, and until such agreements have been concluded, nothing in this Chapter shall be construed in or of itself to alter in any manner the rights whatsoever of any States or any peoples or the terms of existing international instruments to which Members of the United Nations may respectively be parties."

17. This view is further confirmed by resolution 9 (I), adopted by the General Assembly on 9 February 1946, and by the fact that the General Assembly is not able to take any action or to give any directions with regard to the Mandate for South West Africa unless and until the Government of the Union of South Africa submits a trusteeship agreement for that territory.

18. In the case of Palestine, the Mandatory Power has not negotiated or presented a trusteeship agreement for the approval of the General Assembly. The question, therefore, of replacing the Mandate by trusteeship does not arise, quite apart from the obvious fact alluded to above that the people of Palestine are ripe for self-government and that it has been agreed on all hands that <277>they should be made independent at the earliest possible date. It also follows, from what has been said above, that the General Assembly is not competent to recommend, still less to enforce, any solution other than the recognition of the independence of Palestine, and that the settlement of the future government of Palestine is a matter solely for the people of Palestine.

19. The Palestine question was brought on the agenda of the General Assembly as a result of a reference from the Mandatory Power asking the Assembly to make recommendations, under Article 10 of the Charter, concerning the future government of Palestine. Article 10 provides as follows: “The General Assembly may discuss any questions or any matters within the scope of the present Charter ... and, except as provided in Article 12, may make recommendations to the Members of the United Nations or to the Security Council or to both on any such questions or matters.” Mandated territories are within the scope of the Charter but, as explained above, the United Nations can assume jurisdiction with regard to them only when the provisions of Chapter XII of the Charter are applicable and the formalities laid down therein have been observed. These limitations apply to the powers of the Security Council as well as to those of the General Assembly.

20. The position with respect to the consideration of the Palestine question by the General Assembly has changed radically since the receipt of the original request of the United Kingdom. The representative of the United Kingdom informed the Ad Hoc Committee, at its second meeting held on 26 September 1947, that in the absence of a settlement between the Arabs and Jews of Palestine, the Mandatory Power had decided to terminate the British administration in Palestine and to withdraw its officials and forces from that country. Mr. Creech-Jones also emphasized, and this was re-affirmed in his statement to the Ad Hoc Committee at its 15th meeting on l6 October 1947, that the British Government was not prepared to assume responsibility or even to take a major part in the enforcement of any solution for Palestine which had not been accepted by the Arabs and Jews and which required the use of force for its implementation. In these circumstances, this Sub-Committee is of the opinion that no further action is required of the General Assembly on the original request of the United Kingdom.

To sum up, the dissolution of the League of Nations, and the consequent removal of the legal basis for the Mandate, and the more recent declarations by the Mandatory of its intention to withdraw from Palestine, open the way for the establishment of an independent government in Palestine by the people of the country, without the intervention either of the United Nations or of any other party.

21. In view of the opinion expressed above, no further discussion of the Palestine problem seems to be necessary or appropriate, and this item should be struck off the agenda of the General Assembly. In case, however, the Ad Hoc Committee or the General Assembly take a different view of the matter, and in view of the serious doubts entertained by this Sub-Committee regarding the legal competence of the General Assembly to make any recommendations or to enforce any scheme in Palestine not acceptable to the majority of its population, it would be essential to obtain the advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice on this issue. The opinion of that Court would also have to be sought as to the powers which may be exercised under the Charter by the General Assembly, or by any other organ of the United Nations with respect to the future government and administration of Palestine, with particular reference to some of the <278>recommendations of the majority of the Special Committee.

Legal implications of the plan recommended by the majority of the Special Committee

22. During the general debate in the Ad Hoc Committee, grave doubts were expressed by several representatives regarding the legality of a number of the steps recommended by the majority of the Special Committee and the competence of the General Assembly to recom-mend or enforce them. Those steps include, inter alia:

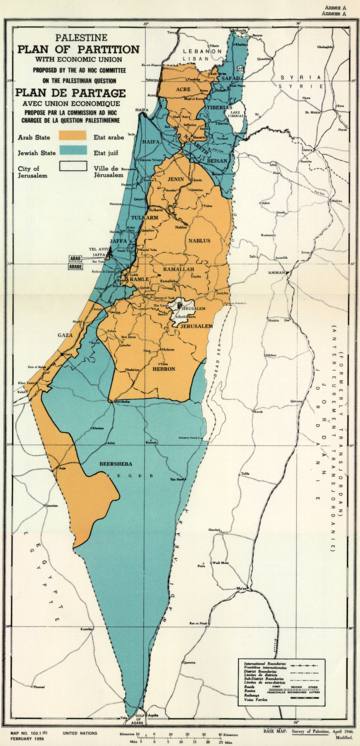

(a) The partition of Palestine;

(b) The creation of an Arab and a Jewish State;

(c) The establishment of a permanent international trusteeship for the City of Jerusalem;

(d) The establishment of an international economic trusteeship for a period of ten years, in the first instance, for the whole of Palestine, in the guise of an economic union.

23. The Sub-Committee considered the legal implications of the plan recommended by the majority of the Special Committee as enumerated above, and its views are summarized below.

The question of the partition of Palestine has to be considered in the light both of the provisions of the Man-date for Palestine, as read with the general principles embodied in the Covenant of the League of Nations, and of the provisions of the Charter. The United Kingdom took over Palestine as a single unit. Under article 5 of the Mandate, the Mandatory Power was responsible “for seeing that no Palestine territory shall be ceded or leased to, or in any way placed under the control of the government of any foreign Power". Article 28 of the Mandate further contemplated that at the termination of the Mandate, the territory of Palestine would pass to the control of “the Government of Palestine”. So also by virtue of Article 22 of the Covenant, the people of Palestine were to emerge as a fully independent nation as soon as the temporary limitation on their sovereignty imposed by the Mandate had ended.

The above conclusion is by no means vitiated by the provisions for the establishment of a Jewish National Home in Palestine. It was not, and could not have been, the intention of the framers of the Mandate that the Jewish immigration to Palestine should result in breaking up the political, geographic and administrative economy of the country. Any other interpretation would amount to a violation of the principles of the Covenant and would nullify one of the main objectives of the Mandate.

24. Consequently the proposal of the majority of the Special Committee that Palestine should be partitioned is, apart from other weighty political, economic and moral objections, contrary to the specific provisions of the Mandate and in direct violation of the principles and objectives of the Covenant. The proposal is also contrary to the principles of the Charter, and the United Nations has no power to give effect to it. The United Nations is bound by Article 1 of the Charter to act “in conformity with the principles of justice and international law" and to respect “the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples”. Under Article 73, concerning non-self-governing territories and mandated areas, the United Nations undertakes to "promote to the utmost ... the wellbeing of the inhabitants of these territories” and to "take due account of the political aspirations of the peoples". The imposition of partition on Palestine against the express wishes of the majority of its population can in no way be considered as respect for or compliance with any of the above-mentioned principles of the Charter.

Moreover, partition involves the alienation of territory and the destruction of the integrity of the State of Pal-<279>estine. The United Nations cannot make a disposition or alienation of territory, nor can it deprive the majority of the people of Palestine of their territory and transfer it to the exclusive use of a minority in the country.

25. The proposal of the majority of the Special Committee that separate Arab and Jewish States should be created is as invalid as its proposal for partition. The United Nations Organization has no power to create a new State. Such a decision can be taken only by the free will of the people of the territories in question. That condition is not fulfilled in the case of the majority proposal, as it involves the establishment of a Jewish State in complete disregard of the wishes and interests of the Arabs of Palestine.

26. The proposal for the establishment of a permanent international trusteeship for the City of Jerusalem cannot be justified under any provision of the Charter. The trusteeship contemplated under Chapter XII of the Charter is, by its very nature, temporary in character, and is intended to assist the people of non-self-governing areas to develop progressively towards self-government or independence as speedily as possible. There is no justification for departing from the original intention of the Mandate for Palestine and of the Covenant, that the whole of Palestine, including the City of Jerusalem, should in the course of time become fully self-governing. The only qualification imposed by the Mandate was that under article 28, the independent government of Palestine was required to agree to certain arrangements providing for the protection and maintenance of the Holy Places in Palestine, but it was never intended that that proviso should be used to limit or impair in any way the authority of the government of Palestine over the capital of its country.

27. The same objection attaches to the proposal for an economic union between the Arab and Jewish States and the City of Jerusalem, to be administered by a joint economic board consisting of three representatives of each of the two States and three foreign members appointed by the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations. The net effect of this proposal is not only to give the Jewish State a considerable say in the affairs of the Arab State against the wishes of the people of that State, but also to authorize the United Nations to take a direct part in the administration of the economic life of the country. In the absence of any trusteeship agreement duly negotiated, there is no provision in the Charter enabling or empowering the United Nations to exercise such authority in any territory.

28. The plan of the majority also provides that the Arab and the Jewish States shall be granted independence only after they have adopted the constitution proposed by the majority, in particular only after they have signed the treaty of economic union. Apart from the intrinsic defects and impracticability of the constitutional proposals of the majority, which have been mentioned in the preceding paragraphs, the Special Committee did not possess nor does the General Assembly possess the power to grant to or to withhold from the people of Palestine their right to complete independence, or to subject such independence to any conditions or limitations. Even the Mandate and the Covenant of the League of Nations contained no such reservations or permanent limitations on the ultimate sovereignty of the people of Palestine. The object of the Mandate, as read with Article 22 of the Covenant, was to render administrative advice and assistance to the people of Palestine until they were able to stand alone. There was no question of imposing any conditions on them when they were able to stand alone or to take away from them any part of their territory.

<280>Views of the Sub-Committee on the enforcement of the plan recommended by the Special Committee

29. The Special Committee assumed that its proposals for the future government of Palestine would be put into effect by the Mandatory Power. It is quite clear, from the statements issued by the leaders of the Arabs of Palestine, as well as by the representatives of the Arab States at the meetings of the Ad Hoc Committee, that the Arabs of Palestine will not be a willing party to this scheme and will oppose its introduction with all the means at their disposal. It follows, therefore, that the proposals can be put into effect only by using force on a large scale and for a considerable period of time. The Mandatory Power declared as far back as 1939 that it could not contemplate a policy such as that of further expansion of the Jewish National Home by Jewish immigration against the strongly expressed will of the Arabs of Palestine, since such policy meant nothing less than rule by force. It was further pointed out in paragraph 13 of the White Paper of 1939 that such a policy seemed to the British Government to be contrary to the whole spirit of Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, as well as to the specific obligations to the Arabs in the Mandate for Palestine. That view was reiterated by the United Kingdom delegation before the Special Committee as well as before the Ad Hoc Committee.

30. If the Mandatory Power found it illegal and impractical to use force to give effect to a policy contrary to the rights and against the wishes of the great majority of the people of Palestine, still less is there any justification for the United Nations to embark on such a programme. It must not be forgotten that the primary purposes of the United Nations, under Article 1 of the Charter, are “to maintain international peace and security”, to "develop friendly relations among nations" and “to be a centre for harmonizing the actions of nations in the attainment of these common ends".

Having regard to the publicly declared views of the various interested parties, the enforcement of the proposals of the majority of the Special Committee can have no other result than to embitter relations between the Arabs and the Jews and to give rise to serious conflict in Palestine. Far from solving the Palestine problem, the solution proposed by the majority would merely tend to create another problem of greater gravity and dimensions.

31. There is another aspect of this case which needs to be emphasized. The forcible creation of a Jewish State within the heart of the Arab world, would not only constitute a serious factor of disturbance within the boundaries of Palestine, but would also jeopardize peace and international security throughout the Middle East. The Jewish State would come into being against the bitter opposition of the Arabs of Palestine and of the inhabitants of the adjoining countries, and would thus create and give rise to an outbreak of hostilities which it may become extremely difficult to check and bring under control. The United Nations would not be promoting the interests of peace and international security by assisting in the creation of a Jewish State, however small.

32. Even were it permissible under the Mandate and the Covenant, or under the Charter, to enforce any particular solution on the people of Palestine, there is no provision in the Charter which could enable the United Nations Organization itself, or some of its Members, to assume power to maintain law and order within Palestine. There is therefore no legal basis for the proposal of some representatives that a voluntary constabulary or police force should be established for the avowed object of maintaining peace and order within Palestine during the transitional period pending the formal establishment of the Arab and Jewish States. Presumably this force would also be utilized for putting down the opposition that is bound to arise to the imposition of the scheme <281>proposed by the majority of the Special Committee. Neither the General Assembly nor even the Security Council can raise a police force of this type for the purpose of enforcing a constitutional settlement, or for maintaining internal law and order, and any such arrangement, by whomsoever it might be sponsored or administered, would be a usurpation of authority and would have no validity in international law.

33. The same remarks apply to the use of regular forces of Members of the United Nations. The General Assembly is not competent to make any recommendations as to the use of such forces, and cannot embark on a programme which would lead inevitably to the use of military force.

As regards the Security Council, while it possesses certain powers for the use of force to maintain international peace or to settle disputes between sovereign States, there is no provision in the Charter to enable it to use its own forces or those of Members of the United Nations with a view to enforcing a particular policy of the United Nations, or to intervene in the internal affairs of any country, whether on the plea of maintaining internal law and order or for any other reason.

34. Before the Sub-Committee concludes the consideration of the legal issues connected with the solution of the Palestine problem, it is necessary to examine, in somewhat greater detail than has been done hitherto, the draft resolutions submitted by the delegations of Iraq. Syria and Egypt providing that some of the legal issues should be referred to the International Court of Justice for an advisory opinion. The draft resolution submitted by the delegation of Iraq (A/AC. 14/21) asks for the advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice as to whether or not Palestine was included in the Arab territories which were to become independent at the end of the First World War, and were to be recognized as such by Great Britain. This question has been put in the forefront of the Arab case all through the Palestinian controversy, and was prominently raised in the discussions of the Ad Hoc Committee. It is imperative that before that Committee proceeds to record any recommendations on the Palestine question, it should arrive at a satisfactory reply with regard to this claim. If the British pledges did include Palestine — and on the available evidence there appears little doubt that they did — the United Nations must respect the pledges, more particularly as the British pledges were repeated in the Anglo-French declaration after the fall of Damascus and Aleppo.

This is a question which involves investigation, both of fact and of law. So far, it has not been pronounced upon by any impartial tribunal. The Iraq draft resolution is eminently fair. During the general debate in the Ad Hoc Committee, no cogent reasons were given to contest the Arab interpretation of these pledges, though it is possible that some members of the Committee might feel some doubt concerning it. The only way of resolving this doubt authoritatively would be to obtain upon this question the opinion of the International Court of Justice. If the Ad Hoc Committee and the General Assembly were to proceed to make recommendations on the merits of the Palestine question, disregarding or brushing aside the Arab claim regarding the pledges, it would give the impression that the United Nations was anxious to record recommendations in accordance with the preconceived notions of a majority of the representatives, and was not anxious to arrive at a just and fair decision.

35. The Sub-Committee, while lending its support to the draft resolution of the delegation of Iraq, would further recommend that the advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice should also be obtained on the validity, the interpretation and the precise scope of the Balfour Declaration.

<282> 36. The draft resolution submitted by the delegation of Syria (A/AC. 14/25) raises four distinct issues which may be summarized as follows:

(a) Whether the provision in the Mandate for Palestine for the creation of a Jewish National Home by means of admission of immigrants into Palestine against the wishes of the indigenous population is or is not consistent with the Covenant of the League of Nations, particularly with paragraph 4 of Article 22 of the Covenant, and with the fundamental right of the people of Palestine to self-determination ;

(b) Whether the majority plan for the partition of Palestine is consistent with the objectives and provisions of the Mandate;

(c) Whether that plan is consistent with the principles of the Charter;

(d) Whether the adoption and forcible execution of the plan is within the competence and jurisdiction of the United Nations.

37. The draft resolution submitted by the delegation of Egypt (A/AC. 14/24) deals with more or less the same issues and provides that the opinion of the International Court of Justice should be sought on the question whether the General Assembly is competent to recommend cither of the solutions proposed by the majority and by the minority respectively of the Special Committee, and whether it lies within the power of any Member or group of Members of the United Nations to implement any of the proposed solutions without the consent of the people of Palestine.

38. The Sub-Committee examined in detail the legal issues raised by the delegations of Syria and Egypt, and its considered views are recorded in this report. There is, however, no doubt that it would be advantageous and more satisfactory from all points of view if an advisory opinion on these difficult and complex legal and constitutional issues were obtained from the highest international judicial tribunal.

39. In amplification of the issues mentioned by the delegations of Syria and Egypt, the General Assembly might, with advantage, seek the advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice on whether the United Nations is competent to partition Palestine with the object of setting up two States; to impose certain conditions in connexion with the attainment of the independence of the proposed Arab and Jewish States; to set up a permanent international trusteeship for the City of Jerusalem; and to administer an international economic trusteeship for the whole of Palestine by means of the proposed joint economic board.

40. It is a well known dictum that justice must not only be done, but must also appear to be done. One of the surest means of securing acceptance of a decision on the part of the parties to a controversy is to create confidence in the minds of both sides that the decision has been arrived at impartially after full investigation of all relevant matters. That the legal issues summarized in the preceding paragraphs are very relevant to the settlement of the Palestine problem will not be denied. An impartial and authoritative decision upon this matter is therefore a necessary and essential preliminary before the Ad Hoc Committee and the General Assembly proceed to make any recommendations on the merits of the Palestine problem. A refusal to submit this question for the opinion of the International Court of Justice would amount to a confession that the General Assembly is determined to make recommendations in a certain direction, not because those recommendations are in accord with the principles of international justice and fairness, but because the majority of the representatives desire to settle the problem in a certain manner, irrespective of what the merits of the question or the legal obligations of the parties might be. Such an attitude will not serve to enhance the prestige of the United Nations, and this Sub-Committee earnestly hopes that the Ad Hoc Committee, as well as the General Assembly, will agree to refer all the legal and constitutional issues connected with the problem of <283>Palestine to the International Court of justice for an advisory opinion.

Back to top